Blender’s Andrew Phillips reflects on a recent, unpublished interview with now-deceased Factory Records founder and 24-Hour Party People progenitor Tony Wilson.

For all the self-aggrandizing and lofty, self-serving liturgy, infamous Manchester TV personality, record guru, and public punching bag Tony Wilson’s most famous quote, the one that echoes through the rafters of every room he ever entered, was a simple, self-diminishing statement: “Don’t tell the truth; tell the myth.”

He sometimes shook it up, replacing the “tell” with “print” or playing minor games with setting and syntax, but from the very beginning of his career — before he helped break legends like Joy Division and New Order, fostered the rise of acid house, or laid the launching pad for modern mega-musicians like Radiohead and Oasis — he had an innate understanding of the power of persona. He realized that, no matter how big his deeds became, the real Wilson wouldn’t be the one that entered unto the ages. That honor would go to the cantankerous creature he’d created.

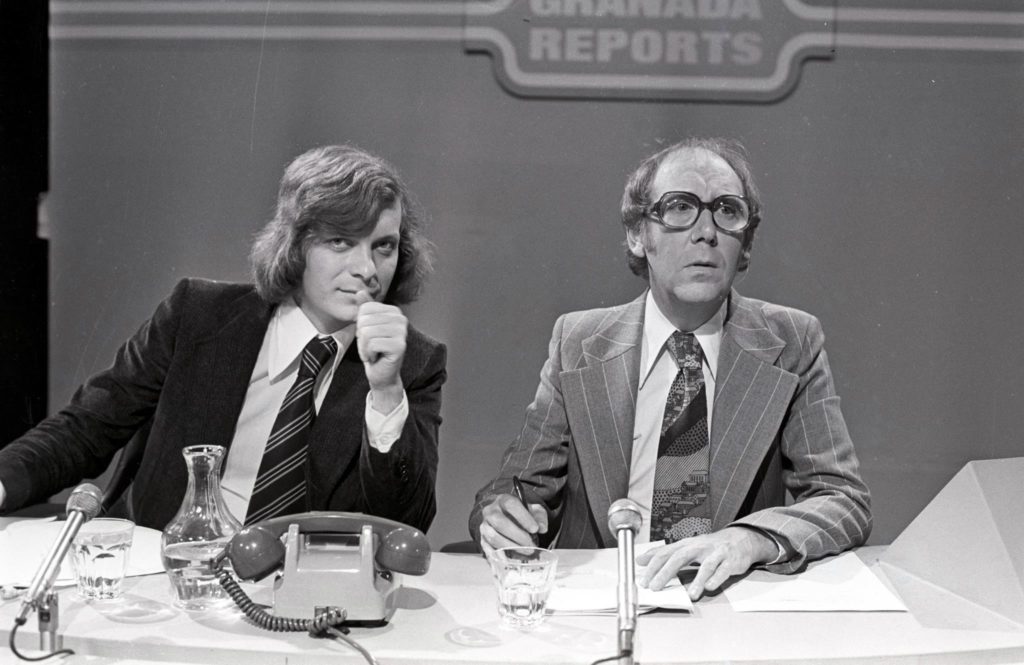

Fostering the rise of his curmudgeonly public persona, Wilson’s second most famous quote was a little less eloquent: “I’m a twat,” he said time and time again, tongue nowhere near cheek. Despite being the founder of Factory Records — an institution that did far more for the advancement of modern music than almost any other ‘80s label — he acted the part of a villain in some seedy neo-noir, dastardly stroking a twisted moustache in an effort to make his minor evils seem all the more epic. His public stunts, outrageous TV antics, and a pretentious public persona made him the ultimate anti-hero — an indubitable dunce that everyone loved to hate. So, if infamy really was what he was after, he succeeded spectacularly: say what you will about Tony Wilson, there’s no question he was a character.

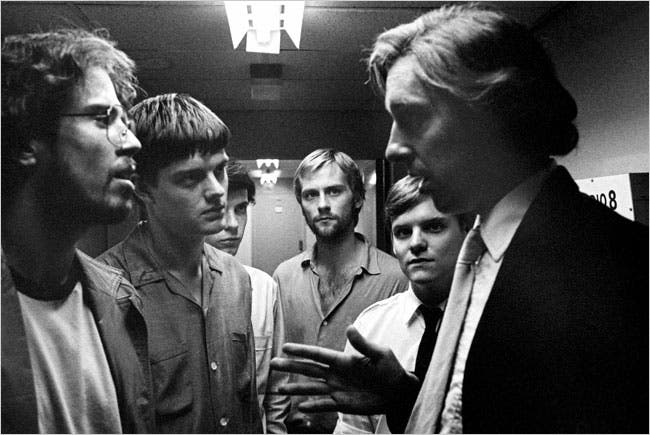

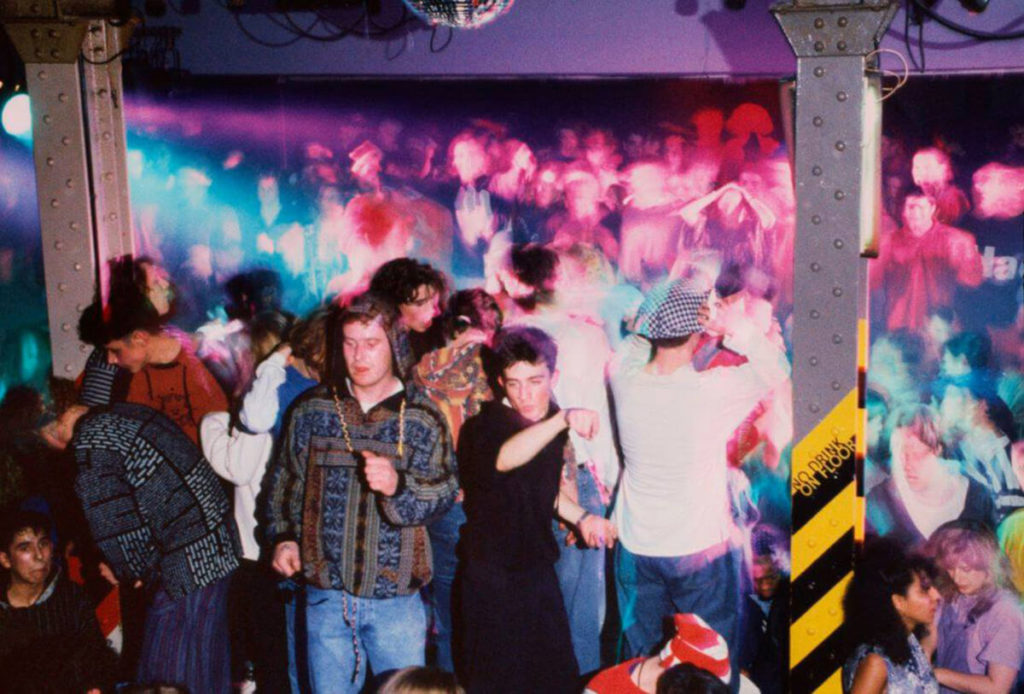

Of course, what’s perhaps glossed over is that fact that he was also an unbelievably action-orientated individual. As founder of Manchester’s infamous Factory Records, Wilson helped hammer infamous post-punkers like Joy Division, New Order, A Certain Ratio, and the Happy Mondays into the world’s collective consciousness. Later, his ill-fated nightclub, the Hacienda, served as the breeding ground for acid house, and its infamous, drug-addled parties became, by many estimations, the birthplace of the modern-day rave.

When both label and club went broke, Wilson helped launch In the City, a UK music-industry showcase which propelled the careers of acts like Oasis, Radiohead, Suede, Elastica, Coldplay, the Darkness, and Muse. And that wasn’t even his day job: throughout it all, he kept a TV gig going, issuing eccentric reports as a reporter and anchor for Granada Television. Though he continued to add to his legend until last week, when he succumbed to complications related to kidney cancer, his early achievements were bronzed in 2002 with the release of pseudo-historical biopic 24-Hour Party People — a wry, self-effacing portrait of a somewhat seedy living legend.

I spoke to Wilson at length some six months before his death. What stared as a simple search for soundbites turned into a lengthy conversation about his ongoing bout with cancer, the fickle nature of public persona, his unrelenting passion for the Happy Mondays, his more dastardly deeds, and how, for all his talent, in person Morrissey is kind of “a cunt.” Only a few weeks out of the hospital after an intense bout of chemotherapy, Wilson was already back at work, preparing for the new American edition of this In the City conference. I was looking for something like 5 good quotes, but he gave me more like 50 (most of which went previously unpublished – there just wasn’t room).

I wasn’t sure whether or not to bring up his recent illness, but, to my relief, he quickly unwound my awkwardness. Indeed, whatever personal pain he felt — and I can only imagine it was immeasurable — he began to talk about cancer not with fear or lofty perspective, but, rather, a sense of mischief and mirth. Before I could even ask, he was delivering somewhat cringe-worthy anecdotes with a slight cackle. He couldn’t wait, for instance, to tell me about how he finally gave Happy Mondays frontman Shaun Ryder — an infamous drug addict about whom he’d spent many a night worrying — a little of his own medicine:

“One of the great things about having cancer and having chemotherapy is that it’s allowed me to get my revenge upon Shaun,” said Wilson. “Shaun has spent the last 15 years scaring the shit out of me by looking like he’s dying. So when he came to visit me in the hospital the other week, by mistake he turned up just as I was having what the doctors call the wiggles… And the poor boy went white with shock. It was great to get my own back on him.”

Indeed, Wilson seemed far more interested in his illness’ effect on others. Ever the king of the off-kilter quote, he did eventually complain about cancer, but in a way that made me laugh a little:

“Last Friday night there was a Manchester against Cancer concert which I was meant to go to and I didn’t,” said Wilson. “I got a phone call from my friend on Wednesday and he goes, ‘Are you all right Ton?’ — because everyone’s very sweet and they ring me up and check how I am. And then he says ‘Are you coming to the concert?.’ And I said, ‘No. No fucking way.’ Because now that I’ve got cancer, everybody fucking loves me.”

What!?!

“So that really pisses me off. I go on telly now and everyone’s going, ‘Are you all right Tony. Are you all right?’ instead of going, ‘Fuck off you wanker.’ I much, much prefer the old Tony Wilson. So, this cancer shit has been a real fucking nightmare. I mean there were three songs dedicated to me during the night. Just fucking pathetic.”

Everything Wilson said had to be taken with a grain of salt, but this response wasn’t all that surprising. Putting things into perspective, he later said, “As my late partner Rob Gretton of Joy Division used to say, this is Manchester. We don’t do gratitude.”

It’s true; gratitude wasn’t really what Wilson was after. He seemed to revel in the thrill of negative reaction. And his ability to act out arrogance is what made him all the more entertaining:

“Because, I’m a local TV presenter; I’m a loud-mouth, arrogant [pauses] shit. So everybody knows me as that, and everyone hates me,” said Wilson. “Well, not hates me — they all like me but they like booing and jeering and blah blah blah.”

For his part, he seemed to enjoy playing public pariah, and it was with pride that he went on to recount a story that, to almost anyone else, would have been cause for genuine consternation:

“Once in the very early ‘70s, when I was a kid on television, Emmylou Harris came in to do a song one afternoon. And I asked her if she’d play a Gram Parsons song that I was very fond of … and she said, ‘No, I’m sorry about that. I’ve got to play my single… That night at a big concert with two-thousand people — fabulous concert; she was wonderful — and at some point between songs after the applause dies down and there’s reverential silence she says, ‘I’m now going to play a song for a young man I met this afternoon. He asked me to play it but I couldn’t. I’m going to play it now. His name is Tony Wilson.’ And before she could say another word, 2,000 people leapt out of their seats and screamed ‘Wanker.’ That is what I am in Manchester, and I enjoy that.”

He did seem to enjoy the attention, and, for its part, the public relished the chance to vilify a snarky public figure. But why would anyone purposely play such a vitriolic villain? My theory is that Wilson always knew he was a far more capable conduit than creator. In <i>24 hour Party People</i>, actor Steve Coogan tellingly observes through the mouth of Wilson that, “I’m a minor player in my own life story.” Indeed, it was as if his persona was part of a public-sanctioned performance.

While he was often branded a braggart, Wilson’s actual achievements were all approached with a modicum of modesty. Be it Joy Division, Happy Mondays, the Hacienda, or In the City, he attacked his projects with unfettered enthusiasm, positivity, and an unflinching dedication to the aggrandizement of others. While he clearly had a sense of his own history, in less guarded moments he managed to be, dare I say, humble:

“To be connected with Joy Division and New Order and the Mondays is something,” he told me in a rare bit of all-out earnestness. “That is very strange for me because obviously Joy Division are one of the most important bands in history.”

It was this seemingly incongruous aspect of Wilson’s character that made the man so compelling. He may have been a self-selling megalomaniac, but he seemed to really care about his acts — and speaking about them suddenly made him seem somehow modest. In our conversation, he waxed ad nausea about the genius of Shaun Ryder, the depth of deceased Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis, and the yet-unmatched production techniques of Martin Hannett. Sure, he was bolstering cred by associating himself with their names, but that wasn’t what seemed to drive the urgency behind his breath.

So maybe all that bad-boy stuff was his way of creating a platform upon which others could also stand. After all, his asinine antics engendered a fascination far more visceral and real than fleeting celebrity fancy, one that allowed him, and by extension those he was helping, a place at the center of public attention. Of course, at the end of the day, he might have also just dug the fact that people thought he was a dick. He certainly went out of his way to leave that impression. But, when I talked to him, it all seemed somewhat disingenuous. He relayed his general rancor without ever actually acting like an asshole, and I found the fact that he called me “sir” oddly endearing.

Of course, in the end, his “print the myth” mantra was unbelievably effective — it helped cement his status as an indie-label icon and extend the breadth of his businesses (though he still never really made any money). Perhaps that’s the final proof that all the misdirection and bloated sense of personal stature wasn’t necessarily about distorting the truth. Reflecting on <i>24 Hour Party People</i>, Wilson told me, “The film just made everything up. It took all the myths and all the stories but in the end, in some bizarre way, it told the truth about punk. It told the truth about acid house, and it told the truth about my mates and myself. It told a load of lies which ended up as a total telling the absolute truth.”

I like the idea that lies can add up to something larger, and I think Tony Wilson did to. After all, his life wasn’t really about him anyway, so what’s it matter if he lied a little?