Plastic People of the Universe: The Dissident Soul of Czech Revolution, Reborn

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Live Review, Writing on September 23, 2020 0 Comments 6 min read

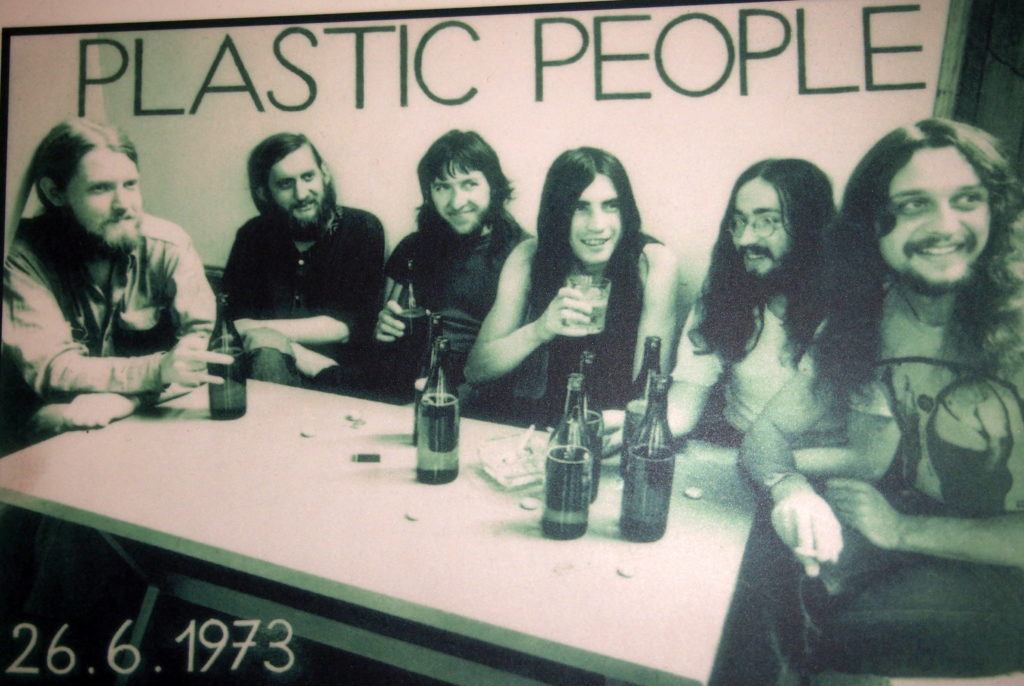

Your average critic becomes a little uneasy when asked to ventue into the realm of cultural historian, but The Plastic People of the Universe leave us little choice. Founded in the ’60s and playing increasingly underground well into the ’70s, this once illegal Czech act was more than a band; it was revolution incarnate.

Not in the Rage Against the Machine sense. There’s no cheesy aggrandizing here, no “Che” t-shirts to be found. These guys were at the center of an ACTUAL uprising. Inspired by western musicians like Frank Zappa and the Velvet Underground, the group was banned in Czechoslovakia soon after the its late-’60s debut for being too experimental, too political, and too “Western”. Thus, they were forced underground by the new Soviet State as part of a policy meant to reign in unsanctioned, fringe culture. (And you thought your band had problems getting gigs!)

“Underground” in this case meant playing secret shows in the woods, at weddings, and on farms — including one in future President Vaclav Havel’s barn — to evade government persecution. Some of these shows went off without a hitch. But the government was not deemed an all-knowing repressive regime for nothing. They soon caught on, raiding the group’s performances and arresting members of the band. It’s a humbling story, one so strange that it often overshadows the music, which is almost as hard to grasp.

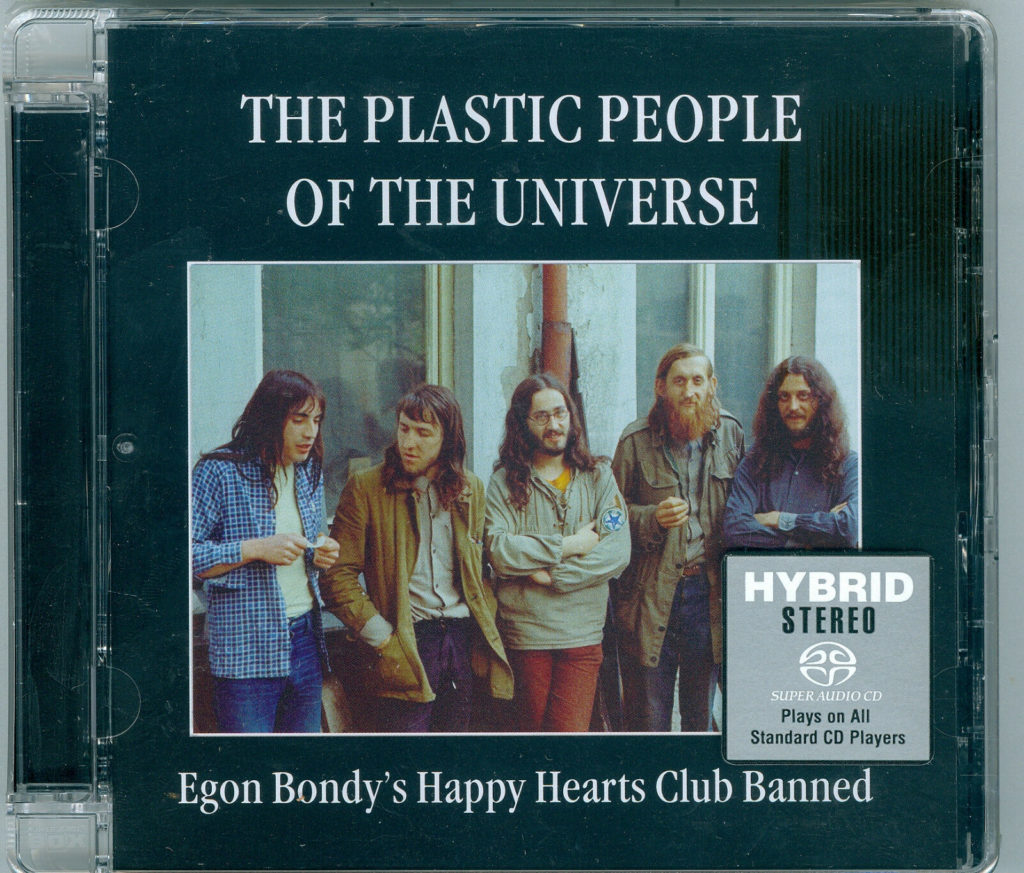

It was truly progressive stuff, akin to work by other innovative artists of the ’70s like Henry Cow and Can. The band’s debut release, Egon Bondy’s Happy Heart Club’s Banned, was contraband and found no official release until years later. It is still only available from the most discerning record stores.

Thus it is that a mix of music scholars/obsessives, Czechs, and the ultra-politically minded caught the band’s rare US performances in the early oughts. Of course, I’m none of these things, just a kid with a friend and a penchant for a good story:

As I worm through the crowd, I’m feeling out of my element. I’m not the only one looking conspicuously out of place. Madeline Albright is quiet. The former Secretary of State is part Czech, a step up on me, but still out of place amidst the tattooed baristas, sticky floors, and thick clouds of smoke. She’s spotted early in the night, immediately shadowed by gawkers. I’ve chosen to leave her alone, but I do catch her personage out of the corner of my eye as she walks over the club’s tiles, passing genuinely unperturbed over the space where my friend’s sister threw up last week.

So it’s me and Maddy, each a little on edge, feeling out the unfamiliar landscape. Well me, Maddy, and the Plastic People of the Universe. After a ruckus performance by DC’s own dissident, apolitical musical revolution, the Rude Staircase, a 10-plus-piece freak-out orchestra of epic intent, the

Plastic People take the stage. Bassist Milan Hlavsa is noticeably absent — he passed away in 2002 — replaced by a tall, young beauty in a long, tight, red dress. Her presence is an odd contrast next to the weathered, hard-worn exteriors of the rest of the band — thick beards are the standard. Unlike the others, she doesn’t look like she’s ever been to prison.

The band begins with a meaty jam: violin, keys, and horns all played to a thick funky bassline. It’s post-prog euro-fusion, approaching disco-funk at times. This is a nice way of saying that it sounds a bit dated. It is made interesting by interspersion of complex harmonies and sometimes scathingly strange notes. Sax player, and tonight’s reluctant emcee, Vratislav Brabenec skronks out his share of sweet, atonal sounds and the band does manage a certain level of dissonance.

Still, it’s not what I expected: the band’s early work was cacophonous, complex, and strange. But that was a long time ago. This change of course, could be the curse of age, attaching itself to even the most innovative of performers. European rock innovators Amon Duul and Can did the same thing in the late ’70s.

But I suspect another force at work. In the ’70s this was a group of rebel outlaws playing to a host of miscreants and dissenters. Now, they’re heroes. They’re a source of national pride, an international symbol of just dissent. The old material might not play well for more recent, upstanding attendees of their concerts: foreign dignitaries, heads of state like Bill Clinton, and 60 year old patriotic Czech men.

So it’s understandable that they’ve cooled it off, fallen more into standard funk-jazz improv modes. While the band may not bowl over the most demanding listener with the progressive sounds of yesteryear, they’re still the recipients of the audience’s awe. The Plastic People hammer through their set, unapologetic in their funky resolve. The songs are broken by scattered stories, told by Brabenec in fractured English.

There’s a whimsical spirit passing between the performers, a sense that after years of glancing over their shoulders they can now focus more on the performance and less on escape routes. The band members bounce together, forcing old bones into frenzied, impassioned movement. They don’t play like a band with baggage, or one with weighty cultural cache.

They dance through the long jams with light-hearted excitement, each member smiling broadly between songs. After an hour and a half in the spotlight the band disappears. The crowd is significantly lighter, about half it’s initial strength — many must have shown up simply to “see” the band and left content to watch only the first few songs. Albright and I both wait it out though, watching the band reemerge to eager applause. The Plastic People plummet into a final number, undeterred by the waning numbers, by those disappointed with their straight-laced performance.

There may be some discontent amongst the obscurists and aficionados — I heard some of them mumbling as they left — but the band seems utterly content. I agree to a point with their criticisms; it’d be nice to hear that weirdo music relived in its full glory. But, The Plastic People of the Universe have earned the right to do whatever they want. You could tell them to rail against the notes, squawking like it’s the old days, but these guys are pretty stubborn. If they wouldn’t soften their resolve for the Soviet bloc, what chance have we got?