Lost Library Privleges

What happens when the need to preserve flies in the face of family?

What happens when the need to preserve flies in the face of family?

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Writing on January 1, 2023 0 Comments 13 min read

My father became a high-school librarian the year I was born. Each birthday brought a tick to his tenure, another 12 months of his rule over rubber stamps and drawers of confiscated pornography (the library was where, at nine years old, I first saw “real” breasts).

I remember visiting the tall brown stacks in his library, their reflection distorted in the wall-to-ceiling panes that separated the wide room from the hall. I would stare across the shelves, always ending up at a dusty, hardbound copy of Have Spacesuit-Will Travel, set off like an exhibit, on top of a shelf in the far corner. I thought that someday I’d filch the book and figure out why my dad kept it on display.

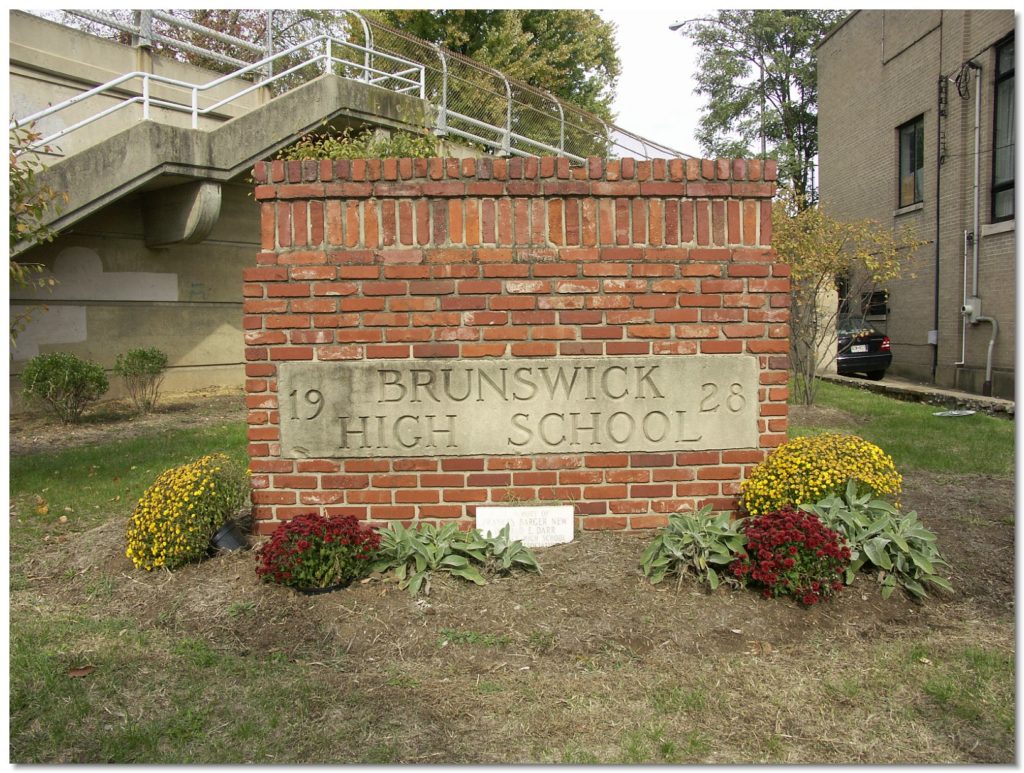

I was in awe of my father’s domain. When people asked what I wanted to be when I grew up I told them, “I’m going to be a magician-musician who works as a librarian at Brunswick High School.” And I would have been good. By the time I was ten I knew the ins and the outs of the library biz and, most importantly, I knew the code. Farmers’ sons learn the Protestant work ethic. Me? I was bred with an understanding that those who accrued late-fees were the utter dregs, the true scum of the earth — “one step above guidance counselors who give out lollipops to bullies,” my dad would say.

I distinctly remember my father’s threat: if he ever found out I had late charges or lost something from any library, he’d tether me to a bookshelf and toss me into the ocean. And we lived four hours from the beach.

I understood the rule. The library was for everyone, its purpose to preserve the past and present, to subvert those who would hoard knowledge by allowing blind, equal access to it. And for this concept to work, its rules had to be respected.

He held himself unflinchingly to the rule. His minor indiscretion, his only wavering point, was “borrowing”non-circulating magazines, lightly delivering glossies like People and Entertainment Weekly into my mother’s hands. Not one to go too wild though, he would whisk them away in the morning to see them neatly returned to their shelves.

*

In college I met Sam, and Sam loved libraries. I never got behind the idea that pots could only be stirred with wooden spoons, but his care for borrowed materials was one of our shared obsessions.

When we first hung out, and later when we lived together — far from the spit-shined D.C. monument district that had been our college home — he’d often carry a stack of LPs under his arm. This excited me to no end. Since leaving my parents’ home I had honed a passion for vinyl that matched my love for books. Sam had a similar addiction, spurning CD’s for the warm, full-bodied sound of old LP’s.

One fall evening, a few months after we moved with a mutual friend into a townhouse, he pressed a stunning avant-grade string quartet to my turntable and described the record’s secret source: the main downtown branch of the D.C. Public Library. He spoke of towering stacks of old LPs that lay downtown, completely forgotten.

“Good stuff,” he said, explaining that in the ’60s some rogue librarian had gathered a host of obscurities: 40-year-old collections of the “new” avant-garde music. Now, they waited in dusty sleeves — the vinyl itself pristine and gleaming, a plastic sheen still radiating from its surface.

A library? Where you could borrow vinyl? I had to see it.

And so Sam took me.

One morning we hopped on the bus, clinging to the overhead rail as it made a straight bee-line down Georgia Ave shifting into 7th and snaking through Chinatown — practically door-to-door service. Inside, the ceilings reached strangely high, the cold empty spaces of modernist architecture. The people though — a mix of loud children, annoyed old men, and sleepy bums — gave the place a soft texture, discernable warmth amidst the coldness of the entryway. The elevator was always out so I followed as Sam deftly maneuvered the long halls, sneaking through back staircases. What he had said was true: deep in the back corner of the library’s second floor were two long shelves packed tightly with dusty old LPs.

Call numbers on placards jutted from the stacks, offering little in the way of orientation. There was nothing to do but dig in. An hour of searching unearthed a whole section of obscure avant-garde records, countless weird blues and folk LPs, and a host of jazz and rock standards.

I made my way to the check-out counter with a towering stack, a smile masking my insecurity. Technically, there was a six LP limit and my pile pushed way beyond the bounds. As I approached the librarian, I imagined my dad’s waggling finger. Though it was an archaic rule, a relic of the past scarcely remembered by those behind the counter, it still felt strange, even with a librarian’s implied acceptance, to break it.

*

Sam and I took to weekly Saturday trips to the library, but one afternoon I found my way there without him, and so I was alone when I found it.

When I got home, I called up our staircase, propelling my voice along the exposed brick wall, around the bend, and into Sam’s room on the second floor. In the electronic avant-garde section — this area had been focus of our collective attention for some time — I had discovered a strange relic, one that demanded his immediate attention.

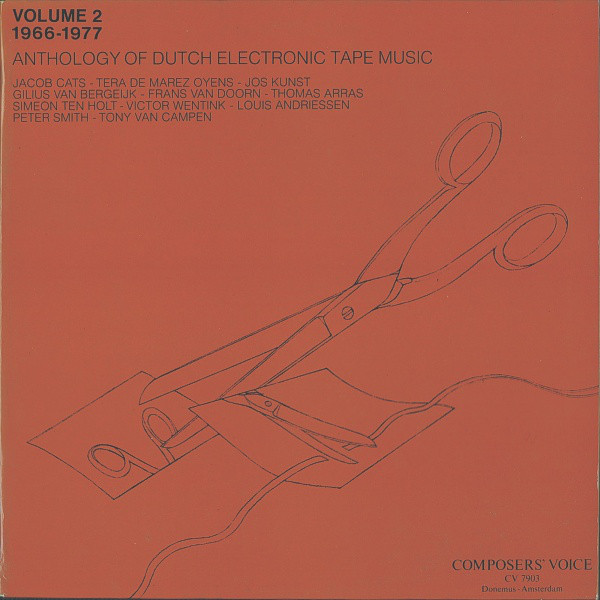

He screamed from the top of the stairs that the name sounded familiar, like something he had picked up last week. We met in my room, to our surprise, each brandishing copies of the same record: Anthology of Dutch Electronic Tape Music: Vol 2.

Sam said he had gotten his copy a week ago but that it was worn with wear, too scratched for reasonable play. Feeling like a doof — so much for my discovery! — I sheepishly slicked the record from its sleeve and dropped it onto my turntable.

As the LP began to spin we sat cross-legged the floor in anticipation. My speakers began to issue adventurous tones, subtle variations in sound that built into inspired, sometimes terrifying, conglomerations of nasty, dissonant vibration. We had heard tape-music before. It was hot stuff: championed by mid-century sound professors and composers, the “music” was created by speeding and slowing magnetic tape and film reels to create strange sounds — sort of like playing with the rewind button on your old walkman. We had taken in plenty of the genre’s blips and bleeps, but we had never heard anything like this. Noises slid across the room lacing through one another in frenzied, wild bursts.

Thumbing through the record’s booklet we learned that what we were hearing was a compilation of ’60s work by of Dutch academics and composers, a serious study meant to display the far-reaching potential of early electronic sound. We were dumbfounded by these experiments. Before the record left the platter, one thing was clear: We couldn’t give it up.

So Sam and I began to trade the record back and forth, one picking the good copy up from the library after the other dropped it off. We carried on like this through the winter. Sometimes we’d get both copies out and trade the good and bad between us. As long as we did this, the record would never get away.

*

As the winter unfolded I was filled with a burning desire to understand where the record had come from. In true aficionado (geek) fashion, I set out to discover its origins. A Google search added no insight; of the record itself I found only three mentions: one, written in German, remains a mystery while the other two were requests on record collector’s wishlists. I looked for it in collector’s books, scanned the library and asked around, but to no avail. The mystery grew despite my best efforts to solve it.

At some point Sam told me he had considered stealing the record, but he couldn’t reconcile the moral implications. He asked me what I thought. Considering what my father would say, I agreed that it would be wrong: “The library’s purpose is to preserve things like this, to allow their access to everyone.”

And besides, as long as we kept carting down to the library, the album was as good as ours.

But, as I searched, failing to find any mention of its existence, any tell of its creators, I began to question my logic. I wanted to have the record, to share it with others, to exhume it from its dusty downtown graveyard. I came to realize that our patronage was the only thing keeping it alive.

And when spring rolled around, after I had made a decision to move to New York, my unfocused desires finally became one clear thought: if I left the record behind, I’d be abandoning it to obscurity.

Sam could have the bad copy. His interest had largely waned anyway — he was on a Gregorian chant kick — and he could still get to the music if the desire stuck him. As for the other copy, something had to be done. I had to save it.

I had to steal from the library.

*

The plan was simple: I’d check the record out and leave it out of sight, out of mind, until a few days before my move. Then, the day before I left, I’d report it missing, clear my account and skip town. I wouldn’t touch it until I was well past the point of no return.

And so, weeks before my move, I quietly signed the record out as normal and nervously placed it behind my dresser. I couldn’t bear to keep it in the open; I was wracked with guilt, thinking of my father’s eyes upon me. And, there was Sam to consider. If he got wind of my plot he would surely chide me, and one light word is all it would take to shatter my resolve.

The space behind my dresser, the implication of the item behind it, roused my thoughts whenever I looked at it. I took to avoiding that corner of the room, but that didn’t help. Some days, I’d come home expecting to find a library tribunal waiting for me, figures with badges and pursed lips: “Shhh” I’d hear this mob of crazed archivists say before they announced that they knew all about my little scheme. I could just imagine them stripping me of my card and its privileges as my father, in the center of the mob, just turned away, shamed.

Of course that didn’t happen. For all my nervousness, my shaking fear, the LP sat quietly, unplayed, behind my dresser until the day before the move.

That afternoon, the room began to empty as boxes swallowed my belongings, CD cases and old sweatshirts cast quickly into cardboard. Soon all that was left in the room was my bed, my desk, my dresser, and that one other thing.

It was time. I took the bus as usual, cutting quickly from my home to the library. The early summer sun beat the ground as I made my way by foot down the last block. This was my last trip to the library, and for a moment, I felt a sense of grief; this was when I realized I was really leaving D.C..

It wasn’t until I passed through the library’s doors that I thought about what I’d come to do. A wave of fear was followed by a sudden sense of premature regret. I silenced it, slowly breathing in and out, and thinking, “it’s a small stupid crime. No one will ever know.”

The security guards greeted me kindly, taking a leisurely look through my bag. I stared forward, no longer shaky with the thought of my crime. Making my way through the metal detector I shot straight for the counter. There was a queue, so I took my place, biding my time by picking at my fingernails.

When I was called to the end of the desk I cleared my mind of shamed thoughts and moved quickly, blood bursting through my ragged fingertips. Stuttering, I spoke the words, “I want to clear out my account. I’ve lost a record, and need to take care of it.”

Martin Luther King stared from the plastic of my library card as the woman at the desk ran his head through the scanner.

“There’s a problem … .”

This was it, the jig was up.

” … Even though it’s one of our older records, you still have to pay the full $11.00 fine.”

“What?!”

“I know that seems like an awful lot for an old record. If you want I can call the reference librarian down and see about a reduced fine.”

“That’s OK.” I said. “I’ll pay it.”

*

It’s a year later and Sam has become a librarian (no joke). I made it to Brooklyn, and live in a small apartment a few blocks from the nearest branch of the public library — I’ve already racked up $49.00 in fines.

I haven’t exactly spread the record around much, but I do sometimes dig it out for friends, to ease their curiosity — this tale is an embarrassed one I’ve taken to telling when I’ve had too much to drink.

Each time I play it, I think of my father and of what it means to save something. I consider admitting my crime to him, trying to convince him that what I did was right. Then, I wonder if what I did actually was right. I feebly reflect on my motivation, on what could have been, on my one misstep. I know that I’ll never have a chance to set things right.

And this mistake, it eats at me.

I stole the scratched copy, and it barely plays.