Drenched, nervous, fingers frenzied. The morning’s approach lends a frantic energy, an inexorable hunger for an end to this ruin. Stretched across the good and bad sides of anger and hate, caught inside some strange body, some insomniac’s shadowy skin, I press myself hard, against the full weight of the approaching sun. Please Lord; don’t bring the hammer down, not until I’ve escaped these scattered visions, these long, horrible streaks of black.

Glassy as they are, it’s my will that shatters, not my eyes. In the face of the looming hour I can no longer wade through broken, incoherent phrases set against spliced, superfluous profanities. Unlike my monitor, I’m a blank screen, unable to iron meaning into this jumble of meaningless adjectives. And then, suddenly, met with the right kind of eyes, I see a solution. I delete the writer’s article and go to bed. As my eyes fall hard, I see an image appearing, etched on the back of my eyelids, the graffiti of a less loving self. I watch as the letters form, waiting as the words congeal producing a clear, undeniable thought:

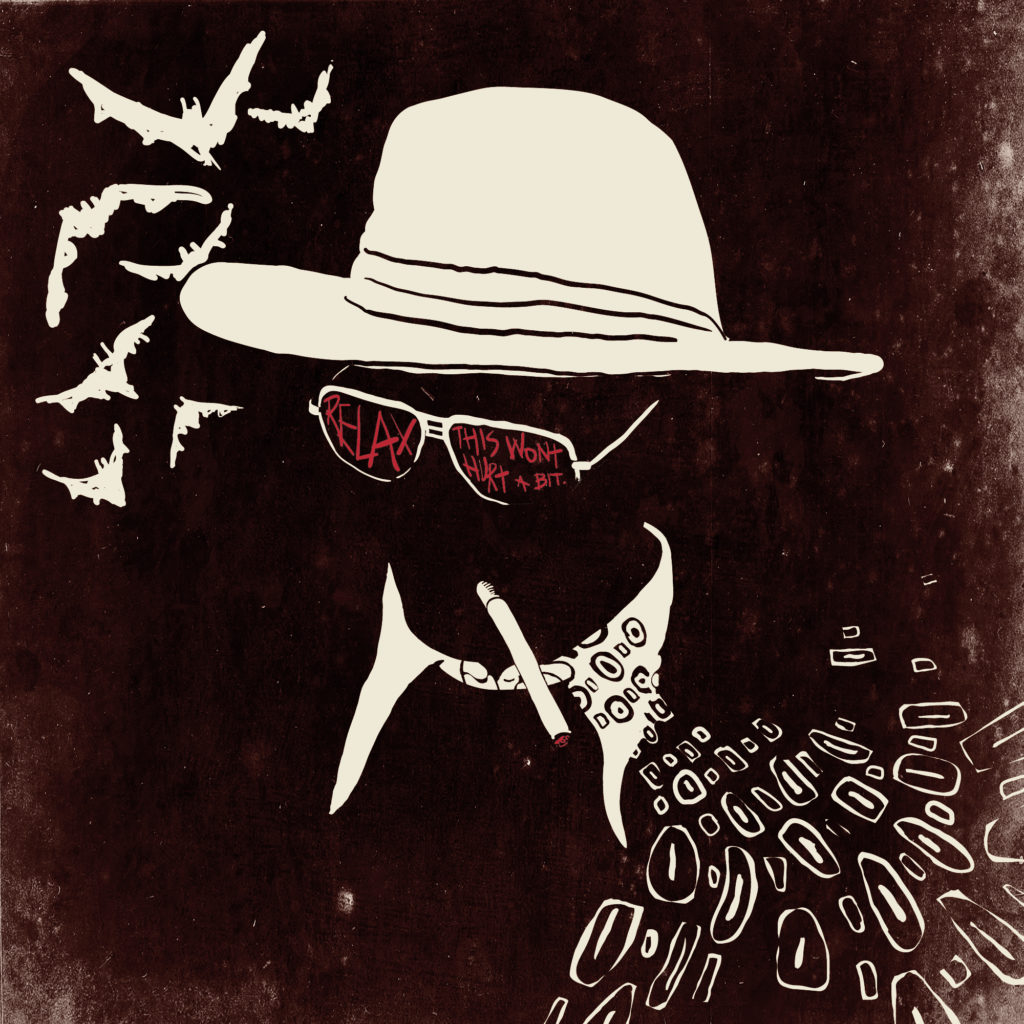

“I fucking hate Hunter S. Thompson.”

* * *

Wait. That’s not quite right, and it’s not how I actually feel — this is, after all, a tribute. I don’t hate Hunter S. Thompson; I hate his contemporaries.

In college I edited writers so enamored with Hunter S. Thompson that without re-reading Thompson’s stories, I could have reconstructed them, in their full glory, reeking as they do with the sooty smell of cigarettes and the vomitous stench of chemical excess. What I couldn’t do was make these rehashes any good.

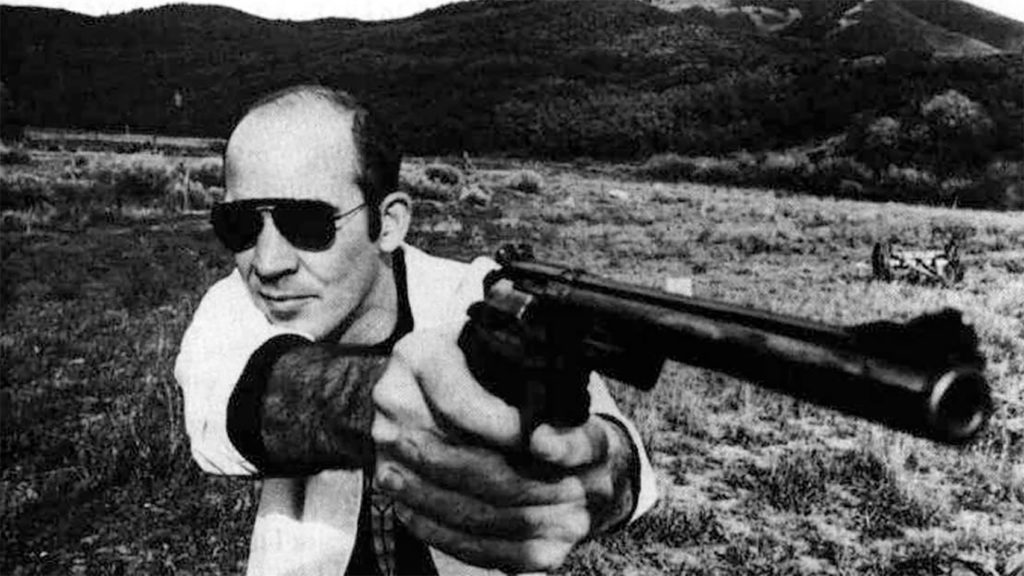

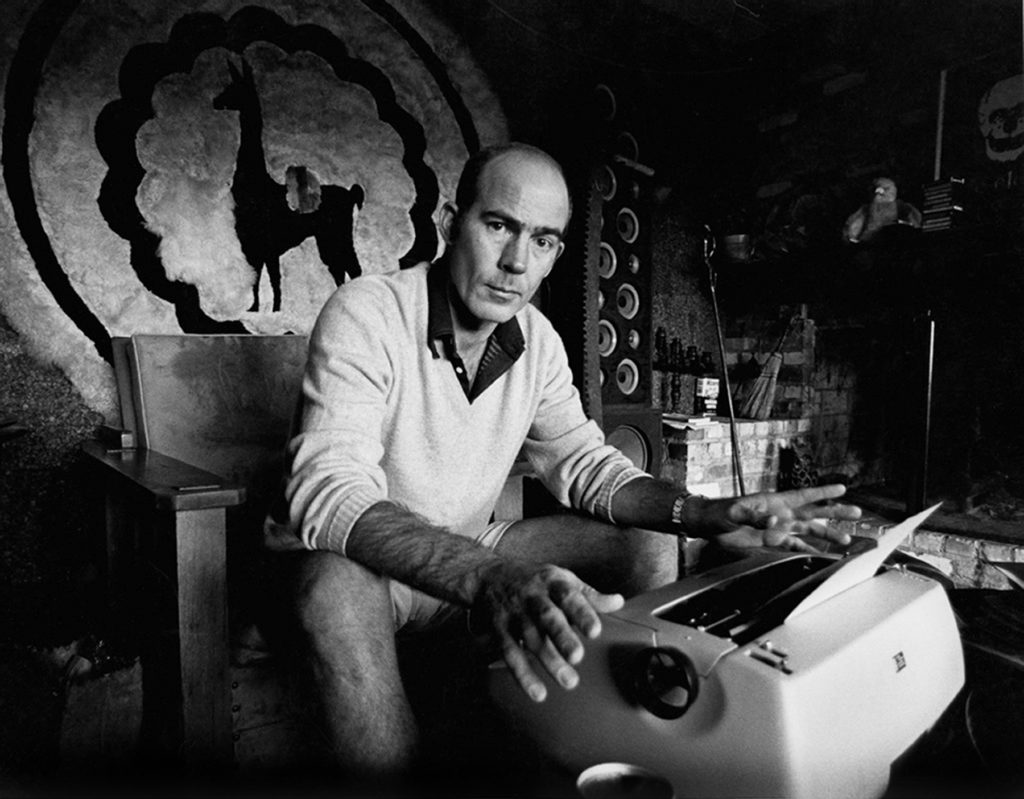

Hunter S. Thompson was a legend; no one’s denying that. He spoke with unabashed honesty, blurring the lines between intrinsic and extrinsic truth. Now that he’s gone, it’s time to start thinking about the deeper cultural meaning or his method, the lessons of his legacy. How do we honor him? How do we, as writers, embody his spirit?

I once met an “editor” who, in the name of Gonzo journalism, eschewed the entire editorial process leaving his writer’s to scribe fiercely, without regard for theme or structure. He in turn presented their work to the world without mediation, unaltered and without edits. His section was edgy, but impotent, a misinformed tribute to Thompson’s literal being, an insult to his essence.

Like many others, what he missed in Thompson’s work, what so colored his failure as an editor, was the deeper foundation of Thompson’s genius. Thompson work wasn’t steeped in the dismissal of reason, the uncalculated condemnation of fact. His writing wasn’t free and uncaring. It was meticulous and calculated. Thompson attacked his subjects with a kind of hyper-scrutiny, exposing not only immediate truth, but also those realities hidden beneath base perception.

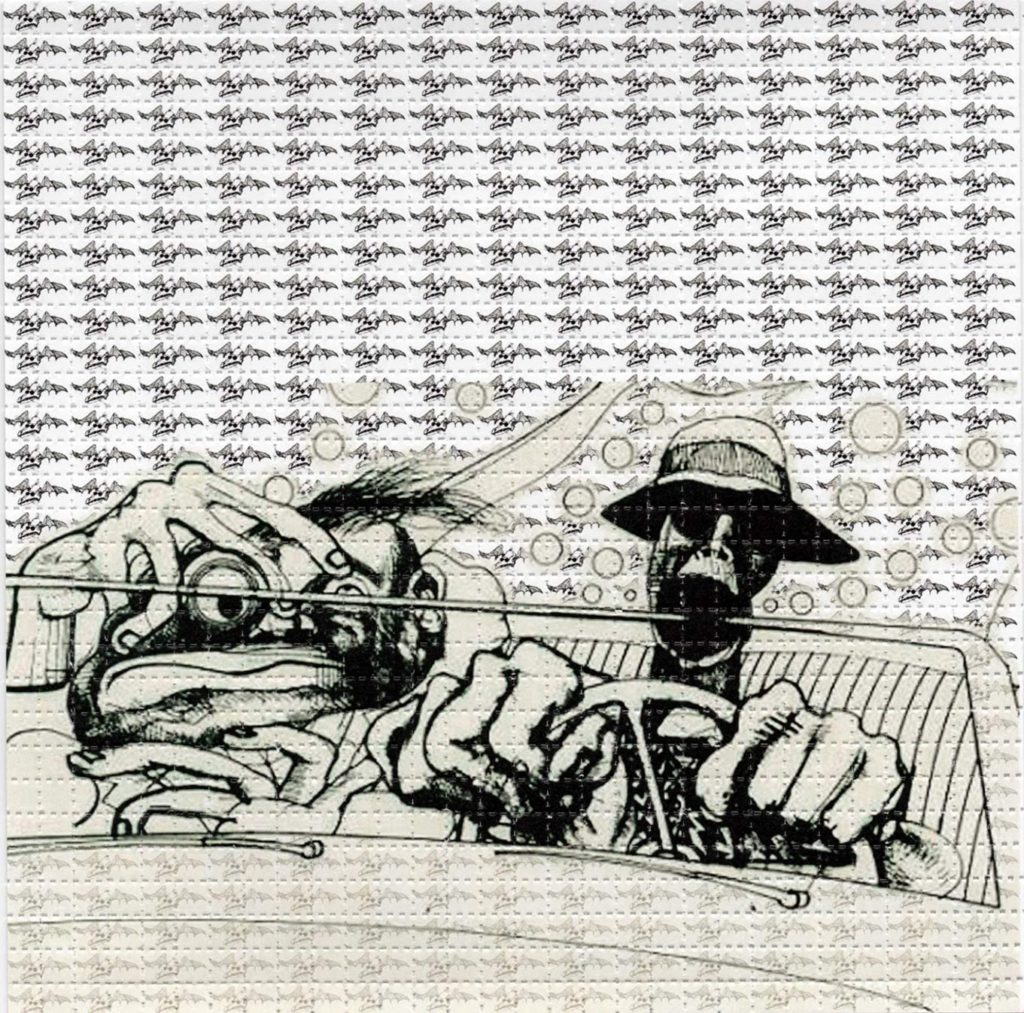

Thompson possessed a singular voice, one influenced by his various delusions perhaps, but not bound to them. Like famous beat writer William S. Burroughs, Thompson’s path through the dreary American underbelly was informed by both startling intellect and knowledge and understanding of conventional forms. It wasn’t the drugs that made either of these writer’s great. It was their inherent ability pressed against the face of that insanity. Thompson did not skirt form, he transcended it.

In the days preceding his “Gonzo” fame Thompson was an astute reporter. Thus, he cut his teeth with more conventional styles before venturing into the outer reaches. When he went “gonzo” he did so willfully and with ease because he understood that which he was rejecting. This is a stumbling block for many aspiring writers, one that made me fear the influence of his writing on my own. Imitation is not revolutionary; it does not reflect mastery. Just as doing heroin offers little aid to those reaching for Charlie Parker’s transcendent tone, acting like an idiot doesn’t lend an aspiring writer a special insight.

I love Thompson’s writing. I’ve spent hours wading through his work, pinpointing the masterstrokes, the unassailable insights. But, he, like his work, is a relic bound to time and place.

When Stravinsky debuted his masterwork “Rites of Spring” his revolutionary use of the bassoon inspired a near-riotous response, loud objections from the audience and threats of violence. Thompson’s words similarly upturned their surroundings, sweeping down with powerful fire. But nowadays the bassoon’s reach is less limited, its use in any form, generally sanctioned. It, like Thompson’s style, holds only the remnant ashes of revolution.

The wind is blowing again, a begging call for journalistic reform. Scandal and alleged bias sweep newsrooms as lines between fact and fiction come once more into question. This is not, however, a call for the Duke’s return.

This generation’s Bob Dylan will sound nothing like the bard himself. The next Hunter S. Thompson will don less eccentric sunglasses and speak fiercely with his own voice in a language unique to this time and place. The most fitting tribute then, to Thompson’s legacy, is to let his work lie with him, and exhume only his rabid hunger for truth. That’s the path of Thompson’s true contemporaries.

If imitation is all we’re after, I say we leave Hunter alone and have another go at classical composition. After all, in the new millennium the Bassoon might lack revolutionary fire, but at least it still sounds pretty.

Fear, Loathing, and Legacy: Why Hunter S. Thompson Ruins Writers

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Commentary, Writing on September 19, 2020 0 Comments 5 min read