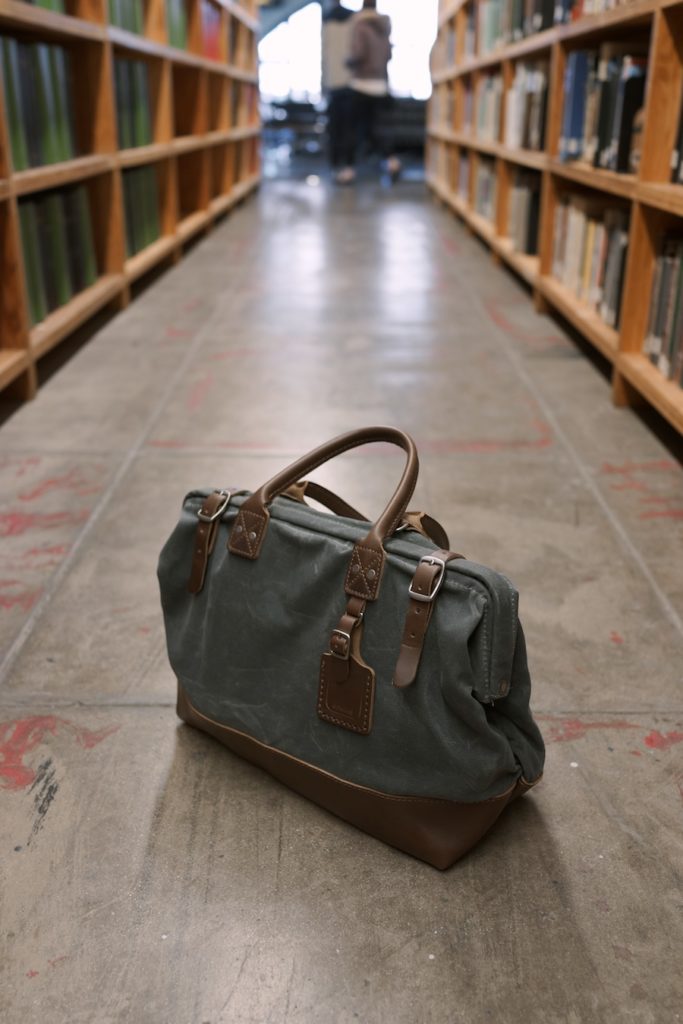

Clothing trends come and go faster than a super-cute fashion-week freebie. But the prominent leather impresarios behind Billykirk simply aren’t interested. Partnering with the Pennsylvania Dutch, brothers Chris and Kirk Bray create a line of handmade leather products that are simultaneously cosmopolitan and relics of a classic age.

Yes, they’ve got a store in Lower East Side Manhattan; yes, they’ve designed for major corporate clients; and, yes, their work has been featured in haute fashion mags around the world. But it’s their old-school approach to leather, and their trademark style in everything from bags and belts to phone accessories that have made them New York kings of rugged wear. Sound familiar? We thought so too. Woodford Reserve champions that same dedication to craft and timeless style, while maintaining a hearty substance.

We caught up with Chris Bray to talk style, design, and how the industry has evolved over the 16 years they’ve been in business.

Flavorwire: It’s interesting to me the way you commingle of urban and rural traditions in your workspace and process…

Chris Bray: There wasn’t a concerted effort to blend the two cultures or aesthetics; we simply liked NYC and wanted to be a subway ride away. We also happen to work with the Amish in Pennsylvania, so there is that interesting dichotomy of having them produce leather and canvas items for hi-tech gadgetry… I remember thinking it was pretty strange that these people who are virtually living in the 1850’s were making iPod holders back in 2004 that they can’t even listen to. Going there for a few days really opens up your eyes to what is really important in life.

FW: Sure, but how do two city boys begin working with the Pennsylvania Dutch?

CB: When we were considering the move to NYC in the early 2000s, we knew that finding affordable rent and workers was going to be a challenge. Luckily I had a colleague who worked with some Amish in PA. I was given a number for a neighbor who kept a phone for the Amish family that did leather work nearby. This scenario is pretty common — where you have a sympathetic family who keeps a cell phone on hand for the neighboring Amish family. So, they essentially sent one of their children down to the Amish workshop and let them know that there was a person interested in their services, and the rest is history.

FW: You’ve said many times that your products are not “trend driven.” Still, every season, you have to prioritize certain ideas/designs over others. What does the process of weeding down look like, as you work out a given catalog?

CB: Trends fade like cheap jeans. We prefer classic, understated looks that aren’t the focus of attention but instead blend into the wearer’s clothing choice. We’ve never been a company to add a bunch of unnecessary trims or garish details (though we did have our moments with studs and rivets early on in California!), but rather live by the words of Harold Nielsen, a famous silver designer who once said, “Ornamentation should emphasize the harmony of the pieces, but must not dominate.”

FW: Is it more challenging to work on spec (or, on a specific commission) or on your own ideas? How do the processes differ?

CB: We do a lot of work with large companies, from Wall Street firms to car and software companies… Those types of commissions are great because we are making multiple items of one color and one style. When it comes to spec work, it’s always easier to take an existing item and rework it slightly with different materials then getting into new R & D with new dimensions, etc. That said, if the ROI is good, the minimums are met, and we feel a connection with the brand requesting the work, then there’s a good chance we’ll get something in the works.

FW: What does “handmade” mean to you now that you sometimes produce for larger, national and international clients? How is the process/craftsmanship different from when you were a smaller shop?

CB: When we started out in 1999, we were making everything. We had a nice little workshop with four or five workers — from a Vietnam vet to a worker from the local Native American outreach facility in downtown Los Angeles. Everything was made by hand… The ship was sailing fine, but then the bigger orders started to roll in — especially the ones from Bloomingdales, Barneys, and boutiques in Japan. These orders simply became too much for us to handle, so we found some established US manufacturers to help out. These guys have every machine imaginable, including 50K laser-driven splitters and banks of top-range sewing machines. We have had relationships with many of them for nearly 15 years. It helps keep overhead down and our design studio leaner and more setup for sampling and shorter production runs.

FW: I’d imagine the biggest challenge in such a creative collaboration between brothers is delineating roles. How do you make decisions when you disagree?

CB: We are both fairly low-key and don’t really take on Alpha personalities — plus we know each other’s strengths and weaknesses, so roles have been fairly well-established. When Kirk, who primarily does the initial design and concepts, is deep into it, I let him roll with his ideas until we are ready to edit. That’s when I swoop in with my two cents and ROI data.

FW: Can’t talk to a leather expert for a Soho culture pub without asking about another group of leather enthusiasts, the kink community. Not many things appeal to cowboys, the urban elite, and dungeon dwellers…

CB: We used to know a guy back in Los Angeles that did a lot of work in the porn/bondage industry back in the day. He was a WWII vet and I don’t think ever understood that culture, but did understand the paycheck. He made a small fortune in that industry. When he retired, we bought up a bunch of his old wide-cuff and various hippy-style cutting dies. He would sell his wares up and down the West Coast in the late 60s and 70s. These pieces of Americana sit in our studio to this day.

Staying Classic in Trendy Times: Chris Bray of Billykirk on Life and Leather

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Commentary, Interviews, Writing on September 22, 2020 0 Comments 6 min read