DC belongs to all of us, but for four years, it felt like it was mine and mine alone.

Needless to say, this is a story of immense white privilege.

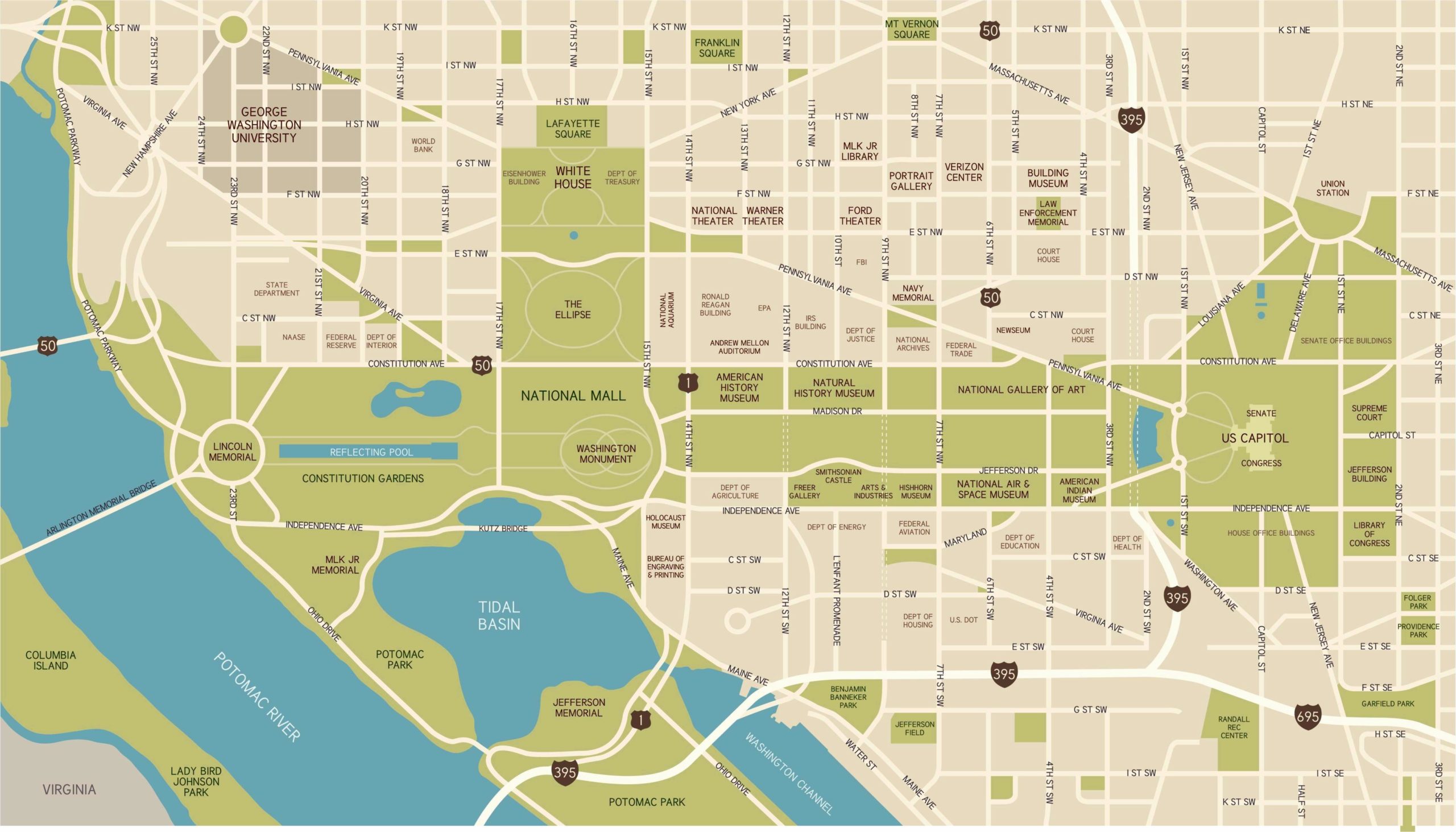

In 2000, at just a tic over 18 years old, I moved into George Washington University’s Thurston Hall, a mega-Dorm for freshmen. That put me smack-dab in the middle of the Capitol’s spit-shined governing district (as opposed to the rest of the city, an oft-ignored multi-cultural beacon of history where the majority of DC’s residents ACTUALLY live).

By foot, my apartment was an equidistant 15 minutes to the White House, the Washington Monument and, best of all, the Lincoln Memorial. Thus it was that the National Mall’s illuminative spaces became as much quad as iconography.

As drunk freshmen tend to do, we lumbered about our domain. We’d lounge of the steps of the Lincoln, sneak late-night cigarettes on the grand brass of Einstein, dare each other to swim the Tidal Basin (no one actually took that one up), and wade into the reflecting pool, a sort of nonsensical reenactment of Forrest Gump’s embrace of Jenny, his lost love.

We’d often play soccer (or, ahem, Frisbee golf) on the greens directly surrounding the Washington Monument. It was bright at 1am, but the circle of lights framing the structure only projected a hundred or so feet out. The result was a relative shadow beginning several hundred feet from the base of the building. You could still see, but it was just dark enough to give cover to quick swigs from our flasks.

It all seemed relatively innocent, but, of course, the inevitable did eventually occur. One evening around 2am, the frisbee was flying wildly outside the circle of light. One had to squint to catch it, so my eyes weren’t wide open when the blinding police spotlight landed on me and the small cadre of folks I was with.

Stoned and terrified, we look back like deer and headlights, unable to see what was assailing us. The megaphone buzz made clear that the cops had arrived.

“Are you having fun?”

Wait, what? With those words, the light went out and we saw that it wasn’t a police brigade or even a squad car. It was a police GOLF CART and the sound we heard was from a megaphone. The words that followed were equally unexpected:

“Can I play?”

That was Officer Link, a park policeman who, it turned out, was not particularly happy that he’d been reassigned to work the monument’s graveyard shift in a golf cart. Given what happened next, it’s surprising he had a job at all. After walking up and getting acquainted, he made a surprising suggestion: “Let’s do donuts.”

One by one or (and at one point 6 at once), we hopped on to the back of his golf cart as he did wild donuts around the Washington Monument. This was a turbo-charged military golf cart (seriously!) and it shot fast enough on my run that I was nearly knocked all the way off.

Over the course of subsequent visits, we got to know Link and he told us things that he probably should not have. Chief amongst them was that at the time there may have been a smattering of rooftop security (aka snipers) in the area, but in terms of monument safety, he was the primary means of keeping things under control. He told us that many nights a single patrol car ran a circuit every 25 minutes around the Lincoln Memorial up to the Washington monument and back. That was it.

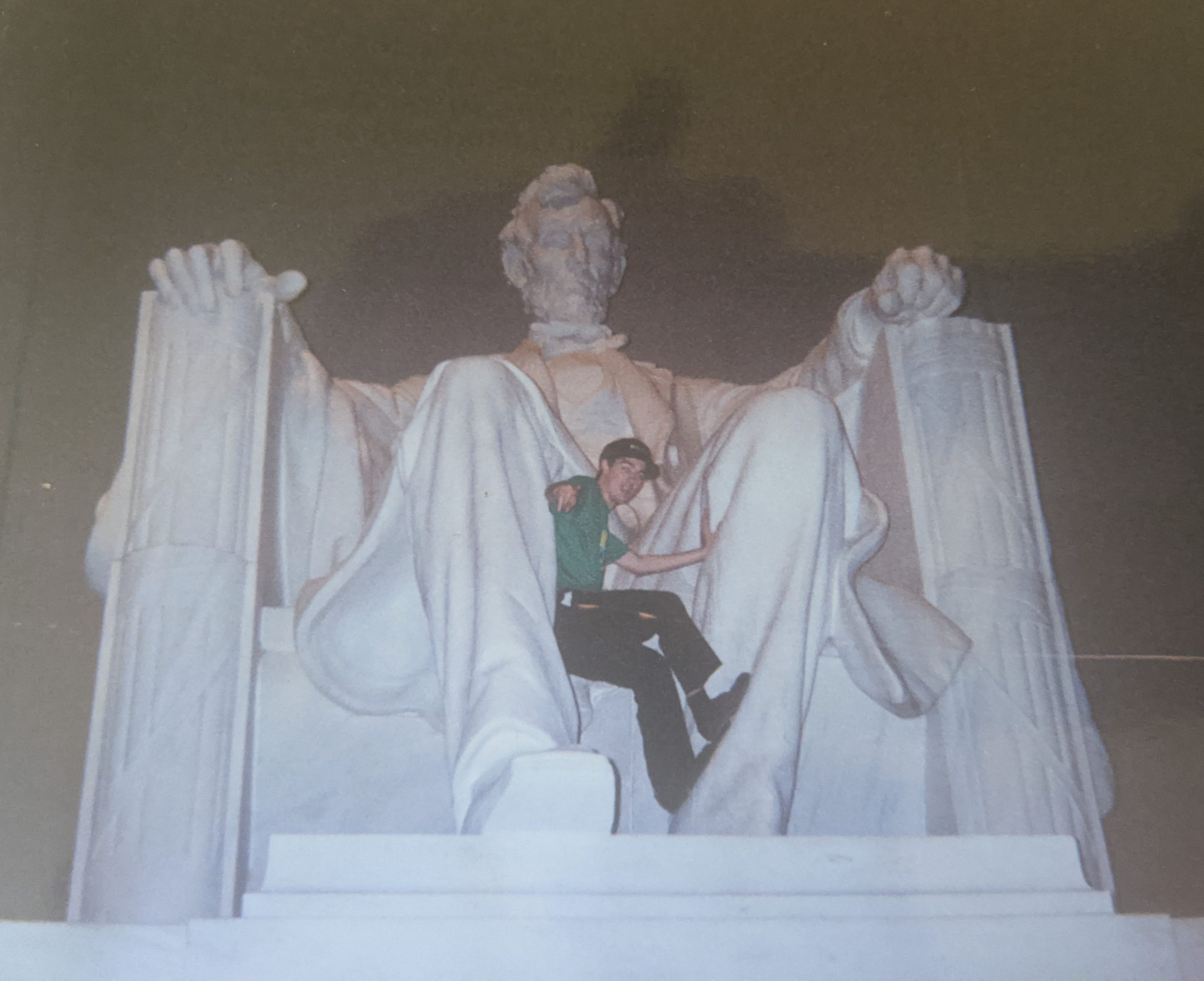

This was useful information for a group of largely innocent miscreants looking to push their youthful exuberance to the limit. One night, we timed the squad car out and, after it had passed, scurried up the legs of Lincoln. It took two friends at the bottom to prop a third up, but once the slick base had been surmounted, Lincoln’s lap was an easy hop up.

At that moment, I thought about Lincoln himself, and about MLK standing proudly in defiance of a racist American undercurrent that would have enslaved him if not for a war that the former had fought. One by one, we climbed, we snapped a few pictures, and we got the heck out. Sitting on the lap of Lincoln left an even greater impression on me than any of my other visits. I probably shouldn’t have done it, but I’d touched the thing I revered and it had not withered or vanished at all.

On our last visit with Link (he was soon to be once again reassigned), he told us that the only thing keeping us out of the Washington Monument was a set of two locks, one to the door and one to the elevator itself.

He had both in his hand. He offered to take us up.

I remember standing in reverence at midnight with a tear in my eye (cheesy, i know, but it’s true). The vast illuminated beauty of the Capital stood below, framed by the powerful and inspiring architecture of the museums along the Mall. In retrospect, the moment reeks of privilege (both white and class), but that doesn’t diminish the profundity with which I approached it. Or the effect it had on me.

Again, I took away an important lesson: Those things we hold reverence for must ALWAYS be remembered to also be real. It’s also a reminder that this country has set certain things in stone, and they are not easily diminished. Or so I thought.

Less than a year later, 9/11 complicated that understanding. I awoke THAT day in a different DC dorm, Lafayette Hall, about ¼ mile from the White House. Though the intended White House attack was thwarted by the brave passengers of Flight 93, people streamed into the streets in fear of it. I remember gathering with strangers next to a parked car with its radio blasting so everyone could hear the breaking news updates. I remember the smoke from the Pentagon, wafting like a faraway (but not THAT far away) brush fire across the water. It was indescribably scary and it forever changed the way I saw the city.

The next day brought the arrival of “enhanced security”. Washington Circle, a few blocks from my home, became a parking point for scores of military vehicles, throngs of large armored Humvees. Soldiers with automatic weapons patrolled the city day in and day out.

A dark cloud had descended on the city’s psyche, one that took years to evaporate. Even though the soldiers were there to “protect” us, the mere fact of their presence made clear that we needed protecting. It also made clear that an US (as opposed to a THEM) had emerged in public consciousness, and that the line of troops was the only thing keeping the two sides

That what followed was a series of tragic and misguided wars doesn’t change the fact that it was a stark, unimpeachable reminder that humans, like democracy, are always very precariously perched.

That strange cloud has returned and it’s unclear how and when it will unravel. The city is again locked down, the Capital has a green zone, and there’s an army of troops packed so tight that they are literally sleeping in the halls of Congress. Benevolent or not, this occupying force has made clear, once more, that another THEM has emerged. We must thwart those things which separates us as American, but that is a big ask, and, sadly, military occupation is understandable, if not ideal. Another tear fell when I first saw the images of an empty mall, a barricaded Memorial. They should have never been as easy to access as they were in my day, but this… well I get choked up thinking about it.

Still, the monuments, like the country, sit where they were, strong and steady. As after 9/11, after the wars in Iraq, after the great recession and in the throes of the worst epidemic since the early 20th century, those spaces reflect and ring with our highest ideals, even if they are, at the moment, inaccessible. That is something upon which to really reflect. . You can touch these things (even if you shouldn’t) and even bruise them up a bit, but I still cling to an elastic sense of America. As long as we hold it in reverence, I believe democracy may be stretched, intruded upon or even bent, but it can never be broken.

SCALING LINCOLN: A Reflection on Patriotism, White Privilege and the Elasticity of Our Ideals

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Commentary, Writing on January 7, 2023 0 Comments 8 min read