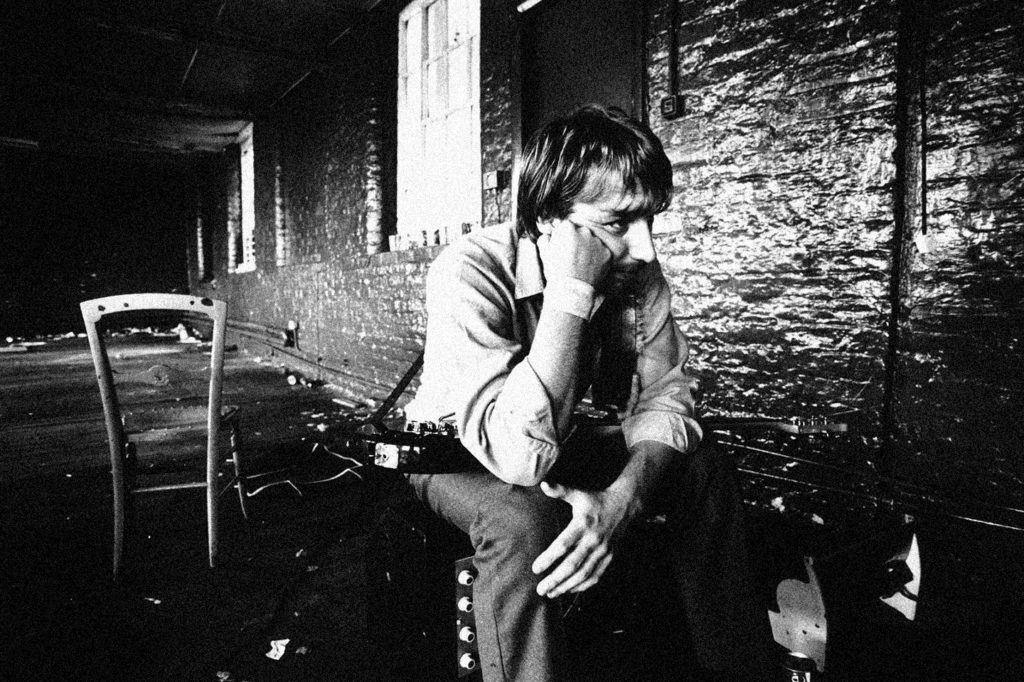

THIS CAN KILL: An Interview With Joy Division / New Order Original Peter Hook

An Intimate discussion of Joy Division, Factory Records, New Order and the tension/dischord that inspired it all...

An Intimate discussion of Joy Division, Factory Records, New Order and the tension/dischord that inspired it all...

By Andrew Phillips Posted in Interviews, Writing on January 2, 2023 0 Comments 7 min read

For a living legend, Peter Hook sure knows how to keep cool. A founding member of mythical post-punk progenitors Joy Division, Hook went on to spend two-and-a-half decades playing to sold-out stadiums as a member of New Order. Between that and the legendary excesses of mid-’80s Manchester, it’s wonder he’s still standing. He lived through Ian Curtis’ suicide, reveled in the hedonistic atmosphere of the fabled Hacienda nightclub, and rode along for the rise, fall, and resurgence of Factory Records. Along the way, he did enough drugs to down a donkey.

To say he’s a man without regret is essentially accurate, but that doesn’t mean Hook can’t put the past into perspective. In contrast to his more brooding, obtuse output, Hook is surprisingly amiable. He’s the kind of guy that pulls you enthusiastically to a corner to continue a long conversation, an affable Dad type that genuinely wants to know every detail of your day.

The Beard caught up with him for an intimate sit-down in Oslo, where they discussed what to do when you suddenly realize your lifestyle can kill and what it’s like to spend every day answering questions about Ian.

Read on for the best bits, and if that’s not enough, scroll down to watch a video of the entire interview.

THE BEARD: It’s been interesting to me to see the resurgence in the legend. Certainly with your book coming out, that’s part of feed that phenomenon. Why, now, is there a doubling of interest in that early era?

Peter Hook: Factory Records’ model was very revolutionary at the time… It was quite interesting because it really is a checkered history throughout the whole thing… If we came to [label founder Tony Wilson] with a song, he’d would say “When do you want to go into the studio? Monday? We’ll put it out the week after.” And I think that’s what Tony, Rob Gretton, Joy Division, New Order, the Hacienda was all about – living life to the full in the moment and not planning. Ultimately that lack of planning brought it down, but what a ride.

THE BEARD: As an artist that’s continued to be successful, to what extent to you see the divide in that legacy, between the stories and the adventure and the pure insanity and the music?

PH: To me, they both happened at the same time, which is the interesting point. The interesting thing about Factory Records was the freedom you were allowed. You weren’t given an advance, you had to earn your living. As a group, New Order had never had tour support, ever.

THE BEARD: So the parties were coming out of your pocket?

PH: Yeah we were all self-financed. And that was part of the headiness of the whole thing. You were totally responsible for your own lives. It was perpetuated by the fact that you were making great music. Our skill as songwriters should not be underplayed. Because it’s the songs of Joy Division and New Order that gave the Hacienda it’s freedom, that gave Factory its freedom. We did that, us four. The songwriters. Sometimes that gets a little overlooked. There is that part of you that sometimes wants to scream, “Without us, none of you would have done anything!” Certainly Manchester would have been a much poorer place.

THE BEARD: Before I was talking to you, I heard someone ask about Ian. How is it to, this many years later, be answering questions that I presume were being asked in the early ’80s?

PH: That’s an interesting question, actually. I suppose it must be a skill. And the thing is, normally I don’t spend all my time taking about Ian and Factory when I’m at home. [laughing]… We as musicians are in a very lucky position that you tend to get a lot of appreciation for something like “Love Will Tear us Apart” that took us three hours to write in 1976. It seems ridiculous, but wow, thank god I did it.

THE BEARD: Joy Division, New Order – these are obviously unqualified successes. They’ve entered into the ages. Is there a sense of concern over expectations?

PH: Yes, obviously, but the thing is every song you write makes the next one harder. You’re cutting your options. When you’d only written one song, it was like the world was your oyster. When you’ve written 350… yaaaar. It does get a bit problematic

THE BEARD: Talk to Neil Young about that…

PH: It’s a weird one, because a lot of the time you can get just as slagged off for sounding like New Order as you can for not sounding like New Order. So it’s a very fine line you tread. But I’ve been very lucky: I’m never short of projects. I’m never short of somebody asking me to do something… I still make music, and now, through doing the book, you’ve actually found another avenue, which is taking about what you did.

THE BEARD: Yeah?

PH: That has been weird. It’s very difficult to get your head round. You took it so much for granted, and so much as being normal. You forget how shocking it is and how surprising your behavior – those stories from Ibiza – are to people who never get the opportunity to live life like that. That is one thing I’ve come to realize. We were very blessed in what we were given, and the opportunities, most of which we squandered. And our bad behavior around the world has become legendary… mainly thanks to 24 Hour Party People.

THE BEARD: The more stories I hear, the more lucky it sounds like you guys were.

PH: We’re lucky we’re still alive…

THE BEARD: … whereas some of your companions were not as lucky.

PH: We lost a few. We lost a lot of people.

THE BEARD: You’ve talked about speaking to the Happy Mondays, about how there’s a line you cannot cross. Were there specific points that brought you to that realization?

PH: When that young girl died… Clearly that was to me the end. It’s like something had gone wrong in the party. It had to stop. Everyone had to go home. You’re like “Ah Fuck.” It’s when you realize that you flirt with things that can kill people. You have to be very, very careful. And we glorified it. Happy Mondays and New Order. Factory. There was a great glorification of drug culture. Now as an adult, I realize how ridiculous that was to do that and how dangerous it was.

THE BEARD: So it was an external thing. It wasn’t a particular night with the band?

PH: No, no. Everyone was in this hedonistic world helped by us having our own night club to be hedonistic in. It’s like an adult playground for us. It really was, and for all the other bands in Manchester. For one night in the Hacienda, you’d go in and it’d be Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, James, New Order – they’d all be partying together… It was commonplace for tourists to walk around the Hacienda and walk into the beams because Ian Brown had just walked past. We were all there together. We were all very much used it as our own personal, private playground. It was pretty wild.