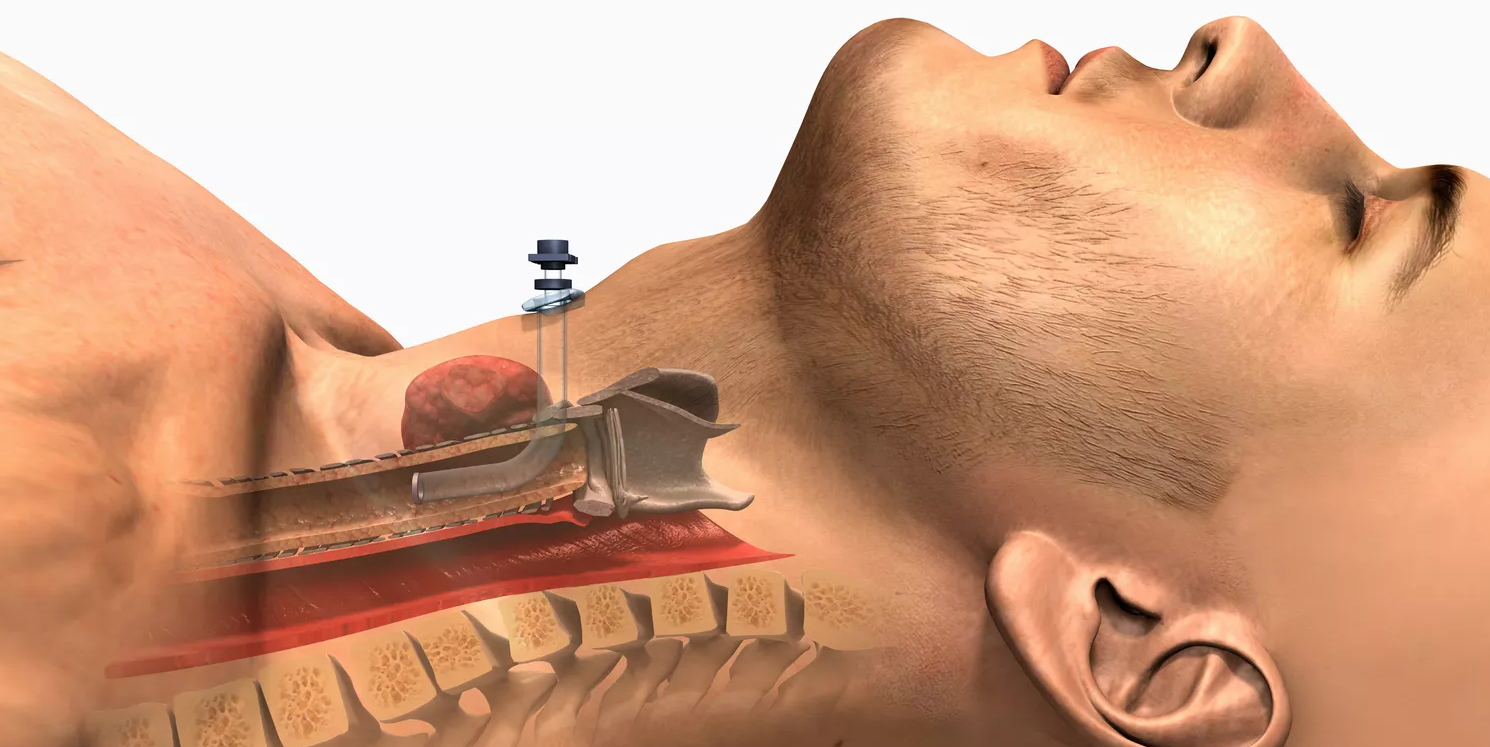

I was on a ventilator once, so close to dying that they actually called a chaplain in (it’s been 10 years but you can still see the cleft in my throat from my tracheostomy).

The doctors told my family to rush back to the hospital, that this really could be it. I, meanwhile, floated in the ether, desperately trying to take in oxygen.

It was a broken night of the mind, punctured by a desperate breathlessness, a tight, dry paste of fear and desperation. It was painful, yes, but what I remember most is the taste of plastic — like I’d inhaled a shopping bag. Almost as if it was lining my lungs, flapping incongruously as air attempted to push them both in and out. That’s how it went as the beepy number machine marched me ever closer to death. In and out. Pain and plastic.

My injuries at the time were so severe that I was unable to move my body or lift anything but my left arm, and even that appendage was pretty precarious. In my fentanyl delirium, I kept knocking the ventilator tube out of my neck. Because I couldn’t speak, I was unable to explain the mistake, and the assumption was that I was trying to harm myself. As a result they tied my only good arm down. At the time, I thought it a great injustice to be denied my only arm, but I now see the importance of playing it safe in life and death situations.

I’m not the authority on covid but I do know doctors and nurses. Over the course of my 40+ surgeries, they spent thousands of hours meticulously battling damage and disease. One doctor spent 15-20 hours in surgery on a 4-inch stretch of my arm alone (delicately attempting to reignite nerves). These people are not given to hyperbole (or sleep), and they’re not about spending unnecessary time with anyone. They face the darkest pockets of mind and body, all day every day, and in my case they were the difference between life and death.

So when THEY say I need to wear a mask and get a shot, it doesn’t feel like a burden; it feels like I’m still not giving nearly enough. People talk about rights, but not so much about responsibility. To paraphrase a recent meme, that kind of selfishness is not an adult mindset — it’s adolescence.

For whatever reason I’m reflecting on that today. I’m trying to reconcile it with the idea that, after the deaths of nearly 650,0000 Americans and 4,500,000 souls worldwide, some STILL think wearing a mask or getting a shot is too big a price to pay to keep others alive (even if there was just a chance it would help). That showing empathy and courage in the face of fear is somehow an act of 1984 groupthink sheepleness. Or that sacrifice for others reflects a lack of savvy or understanding of the world around us.

I just can’t imagine it’s an opinion held by many folks who have actually been intubated, who have nearly died of lack of oxygen. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone, even those so callously acting as if fear and death aren’t gods that hover above us all equally. That humility isn’t the only answer in the face of the unknown.

Let me say that again. There are things in this world that we simply can’t control. So, when challenged by something bigger than ourselves, we survive on humility, not hubris. I didn’t swim all the way into the black (the bravery and love of those around me yanked me back into existence). What I can tell you is that, wherever I was, it didn’t feel much like freedom.